Monetary Policy

Monetary policy refers to the central bank’s regulation of the economic activities through controlling either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (between banks), or via the money supply interventions. The Central Bank will use an expansionary monetary policy to increase money supply when the economy is in recession. This expansionary monetary policy will provide more money to spur investment and encourage more economic activities. In turn, this will increase the aggregate demand. On the other hand, if the economy is facing high inflation, the Central Bank will use a contractionary monetary policy to reduce aggregate demand. This will bring down prices to a more healthier level that can better sustain economic growth.

A monetary policy may be directed towards the ensuring stability of prices of goods in the economy, or it may be concerned with revitalising the economy in times of recession; or even curbing activities when there is a danger of over-trading or over-production.

Expansionary Monetary Policy

When the central bank implements an expansionary monetary policy, it can either reduce the interest rate directly, or it can choose to lower the interest rate by increasing the money supply. Click here for details of monetary policy tools.

When the interest rate is reduced, loans become cheaper and this will entice businesses to borrow more to finance their expansion. In turn, the aggregate demand will increase. If the economy is below the full employment rate, then an increase in aggregate demand will also lead to an increase its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) without much inflationary pressure.

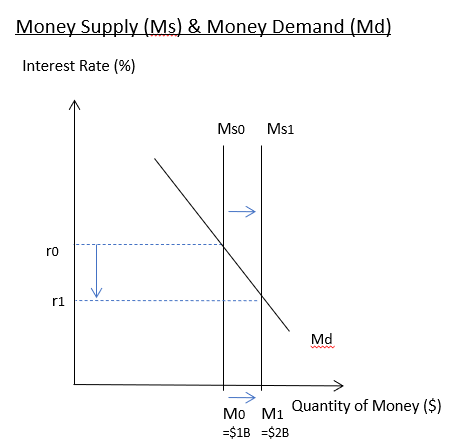

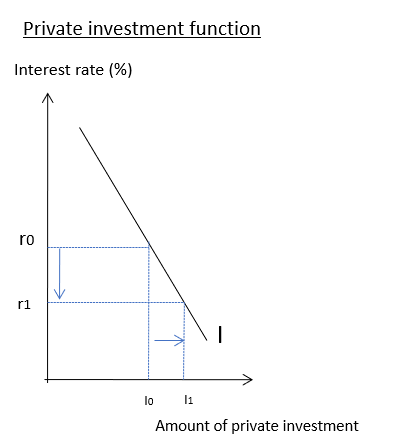

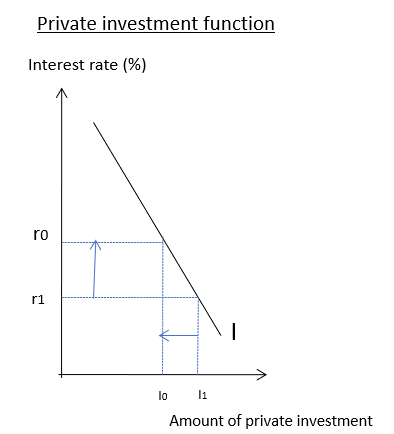

The diagrams below illustrate what would happen when the central bank increases money supply by printing more money. When money supply increase (from M0 to M1), the interest rate will drop (from r0 to r1). This is because to inject more money, the central bank typically buys up government bonds from the market. This process will bid up the prices of these bonds, and its interest rate will drop correspondingly, given that there is inverse relationship between price and interest rate of bonds. When interest rate drops, both consumers and businesses will borrow more as loans become cheaper. The diagram on the right shows the increase in borrowing by businesses (from l0 to l1) as interest rates drops (from ro to r1).

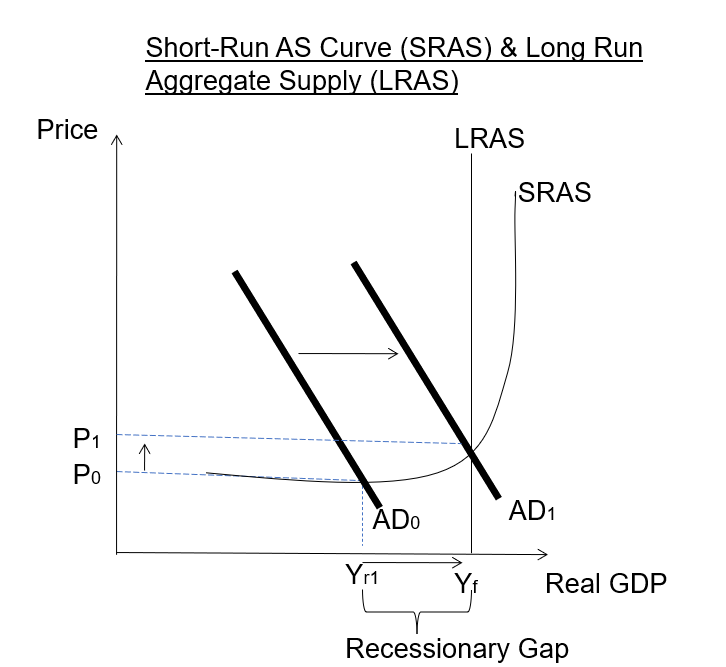

When interest rate drops, both consumer spending and private sector investment will increase. In turn, these will drive up the Aggregate Demand given that it is a function of consumer spending (C) and private sector investment (I) i.e. AD = C+I+G+NX. The Aggregate Demand will increase from AD0 to AD1, thereby closing the recessionary gap.

Contractionary Monetary Policy

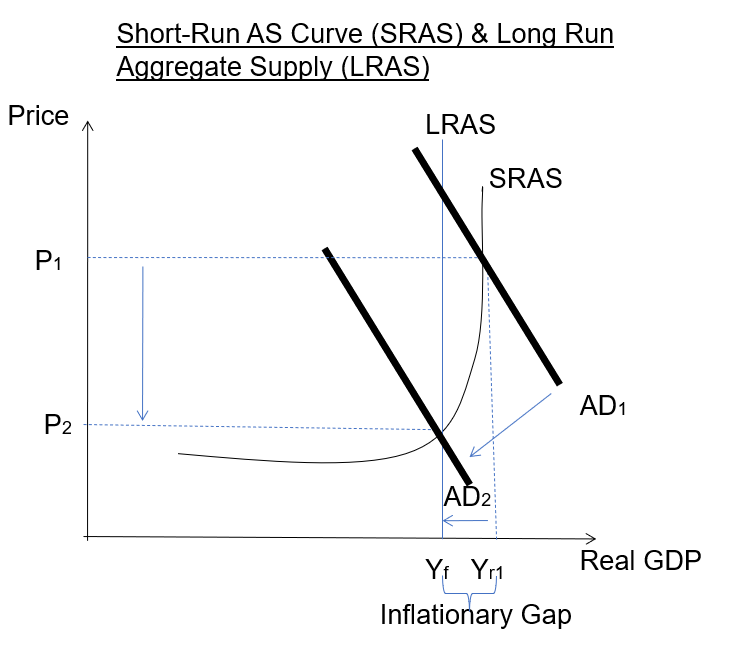

When the central bank implements a contractionary monetary policy, it can either increase the interest rate directly, or it can choose to increase it by decreasing the money supply. When the interest rate is increased, loans become more expensive and this will entice businesses to borrow less from banks by postponing their business expansion plans. In turn, the aggregate demand will drop. Usually a contractionary monetary policy is implemented when the economy is facing high inflation. In this situation, the drop in aggregate demand will serve to reduce the inflation without necessarily diminishing the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

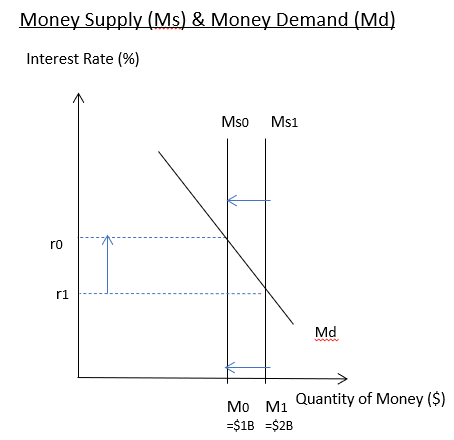

The diagrams below illustrate what would happen when the central bank decreases money supply. When money supply decrease (from M1 to M0), the interest rate will rise (from r1 to r0). This is because to withdraw more money, the central bank typically sell government bonds to the market. This process will bid down the prices of these bonds, and its interest rate will rise correspondingly, given that there is inverse relationship between price and interest rate of bonds. When interest rate rises, both consumers and businesses will borrow less as loans become more expensive. The diagram on the right shows the decrease in borrowing by businesses (from l1 to l0) as interest rates rises (from r1 to r0).

When interest rate increases, borrowing becomes more expensive. This will cause both consumer spending (C) and private sector investment (I) to fall as a consequence. In turn, as Aggregate Demand is a function of these expenditures (i.e. AD = C+I+G+NX), it will also drop, diminishing the inflationary pressure. If calibrated appropriately, the drop in Aggregate Demand (from AD1 to AD2) will allow the economy to reach Yf, its full employment rate.